From a young age, we, as students and young adults, watch others to exemplify how to live our lives. We notice how people look, speak and act, as well as how they are received by others. From these observations, we build our own character foundations and make decisions that become our personalities.

As we grow, we identify and adopt role models, too. Nearly every child has at least one role model, however our role models aren’t always people we know. Role models can be celebrities, historical figures, or even fictional book characters.

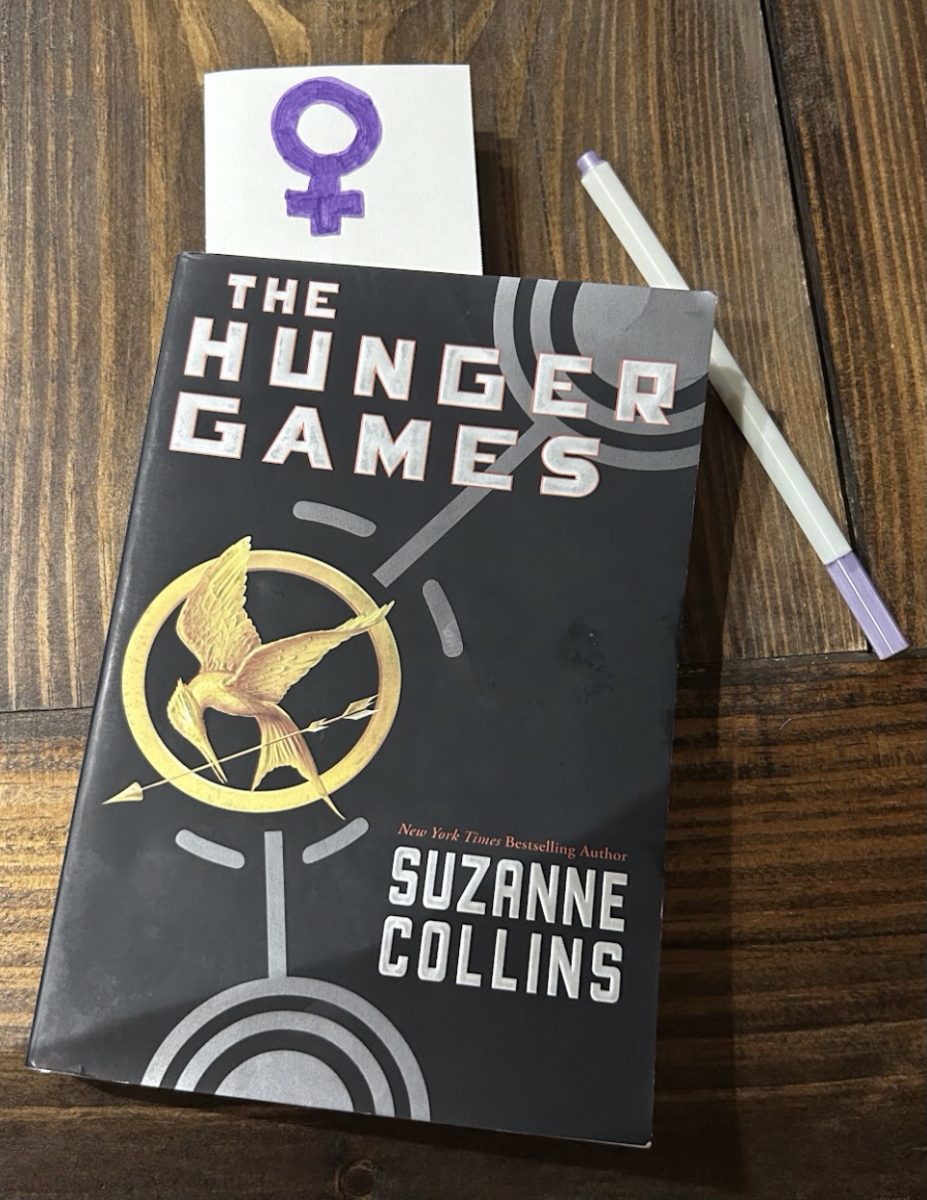

In 2008, Suzanne Collins published “The Hunger Games,” a trilogy full of characters who defy traditional roles and empower readers to do the same. The dystopian novel is set in Panem, a country divided into 12 poor districts plus the rich, extravagant Capitol. Panem’s government hosts The Hunger Games, a televised competition where children are randomly selected (one boy and one girl from each district) to fight to the death for the entertainment of The Capitol.

I was 10 years old when I first read the series. The lessons I took away from that first reading, by observing characters like Katniss Everdeen and Peeta Mellark, permanently raised my self-expectations as well as the expectations I held of others. Watching these characters move through their storylines taught me that being “too strong for a girl” means to have the capacity to help others, and being “too emotional for a man” means to show the people you love that you care.

Now, several years later, defying expectations is something I value strongly. It all started with “The Hunger Games.”

I am not alone in my analysis. Vikki Hogg, Community School of Davidson (CSD) English 2 teacher, believes that “The Hunger Games” impacts the young adult (YA) genre in many ways.

The story “definitely helped broaden the idea of what male and female characters in young adult could be,” Vikki Hogg said.

The main character, Katniss Everdeen, is a prime example. She lives in District 12, the poorest district in her country of Panem, and is hardly the picture of a stereotypical 16-year-old girl. Everdeen is rock-solid, independent, and, at times, cold.

Readers see her strength from the very first scenes. The first scenes include Everdeen soothing her sister from a bad dream and going out to hunt before her family wakes. The immediate impression we get from these scenes is of a “provider” and a “protector,” both masculine roles in a traditional family.

Later, readers learn that Everdeen’s childhood ended with the death of her father when she was 11. Her family starved for weeks while her mother reeled at the loss of her husband. Through the transition, Everdeen became the provider. Readers are clearly told that Everdeen is her father’s replacement in the family, the new “Man of the House,” so to speak.

Traditionally, hunting is one of the most “manly” ways to provide for the family yet Everdeen not only defies stereotypes as a provider, she also shatters perception of perceived limitations of a teenager.

When Everdeen volunteers to fight in The Hunger Games in her sister’s place, she fulfills another popular requirement of a traditionally male character: she goes to battle for her family. This is a major example of her role as the family protector.

In addition to Hogg, CSD student readers see Everdeen as a gender-defying leading character.

“Katniss is a strong, independent woman who fights for her rights as a lower class citizen and saves the others, including male characters, multiple times,” Olivia Cunningham (‘29) said. “She is athletic and wins The Hunger Games with her strength and wits and doesn’t need any man to help her.”

Reading “The Hunger Games” as young as I did initially meant that Everdeen wasn’t a standout in a world of submissive women; she was all I knew. I don’t remember a time when I didn’t believe that girls could hunt, fight, provide, lead and save others.

But Everdeen wasn’t just strong, she was afraid of weakness.

During training and competition, readers see that she is much more skilled with a weapon than her male teammate, Mellark. Mellark’s important skills include disguise (which stems from his experience in cake decorating) and his love for Everdeen (which drew favor for them both among sponsors who watched The Games).

When Mellark confesses his feelings during a televised interview before The Games, Everdeen is furious. She even flat-out says, “He made me look weak,” as a proclamation of place.

Everdeen also has an aversion to all the dresses and makeup she wears in presentation before The Games, though her fashion designer, Cinna, grows on her as a person.

The Capitol also sheds a negative light on fashion and femininity. The people who live there are flat characters who are a picture of the stereotype that women are shallow, irresponsible and frivolous.

The Capitol residents take the stereotype to an extreme in a point of heartlessness and total blindness to anyone but themselves. The most obvious example of this is that they find entertainment in watching The Hunger Games, but the series is littered with notes about their character.

Everdeen, having experienced starvation and extreme poverty almost her whole life, provides the perfect contrast to The Capitol. She is understandably disgusted when, in the second book, she witnesses party guests stuff themselves, induce vomiting, and stuff themselves again. The behavior shows their disregard for (or unawareness of) the less fortunate.

When these ignorant behaviors are paired with initial observations of their extravagant fashion, luxurious lives, and fixation on Everdeen and Mellark’s “star-crossed lovers” story, all signs point to a scathing portrayal of femininity as ditsy and selfish.

The consequences and context of vulnerability, emotion, and “girly” things in “The Hunger Games” had more of a subconscious effect on me than a conscious one. Everdeen was one of the first strong female heroes I read about as a young girl, and I saw her aversion to vulnerability as a protection of her strength.

While one of the first to have a strong female character with this attribute, “The Hunger Games” is an early example of a trend that saw YA become a genre where, according to Aminah Malik, “authors made their female characters ‘strong’ by stripping them of traditionally feminine qualities.”

In hindsight, I thought for a large part of my life that I was the only girl who hated pink because of the traditional stereotype it represented. I shied away from skirts and dresses.

Only recently did I start to understand that I wasn’t alone.

From “The Hunger Games,” the increased popularity of the independent girl who couldn’t have emotional connection or be feminine without jeopardizing her strength affects young readers in a lasting way. Many girls my age have grown up thinking that traditionally feminine things like emotions, “girly” clothes, and vulnerability make us weak.

The interesting offshoot is that this idea is typically pushed onto men. The idea of “toxic masculinity” is a result of the way that men have internalized being told that they shouldn’t need help or burden others with their emotions. Men are raised to believe they are the providers for their families, and the “Man of the House” can’t let anyone see that he might not be strong enough to do that.

When Collins ‘gender-swapped’ her characters, she didn’t leave out gender-specific problems.

“The Hunger Games” is one of the first YA novels to showcase characters defying gender roles. The complicated way Suzanne Collins wrote these characters continues to impact young readers in many ways.

It continues to shape my life, too.