Tate Bruns (‘26) walks into College Prep class and puts her cell phone in a pocket on the wall. Last year, one could assume that if a student put their phone in the sleeve, it was by choice to get extra credit. Students were allowed to carry their cell phones and teachers often used the promise of extra credit to encourage students to put them away during class time.

However, as of July 24, 2024, the Community School of Davidson’s (CSD) new, stricter cell phone policy entitled “No Cells Bell to Bell” uprooted the norm.

In essence, the policy means that students can only use their phones during jumpstart (a 10 minute activity break following two daily early morning classes), class transitions, lunch and before and after the arrival and dismissal bells ring.

Another way of putting it is that cell phones are firmly outlawed during instructional periods.

While instituting cell phone restrictions of the “No Cells Bell to Bell” kind could be considered a hardline stance, Tate Bruns, a new CSD student, had a different perspective.

“They [Hough High, a public school in Cornelius] had the same pockets that we have here. We would walk in and put our phones in before class,” Tate Bruns said.

It worked at her former school and she believes it will work at CSD.

“The policy is great to help people lock in and get [their] work done,” Bruns said when asked about the positives of the policy.

“

Kristen Patterson, a Biology teacher at CSD, concurred with Bruns on the policy’s benefits, adding a few extra details.

“Students are less distracted by their phones, as they are not texting, checking social media, or listening to music,” Kristen Patterson said. “This allows them to be more engaged in class discussions and activities.”

“

Any policy restricting cell phone use and coming down on the perps, so to speak, is bound to be polarizing. It is most likely with that in mind, then, that the administrative post announcing and outlining the policy was written with all sorts of qualifications.

“We know that cell phones and technology CAN (sic) be a useful tool for learning, and the reality is, cell phones aren’t going anywhere,” the July 24 Parent Square post said.

Parent Square is a website that functions as the main tool for communication between parents and CSD admin, and it allows parents easier access to student attendance and grades.

The post also tried to stay ahead of the immediate objections students and parents might have.

“We also know that if we micromanage our students, we aren’t doing our jobs,” the Parent Square post said, knowing that the term ‘micromanaging’ could be used as a pejorative against the policy.

Possibly to acquire more student support, the aforementioned post also used a quote from former student Bella Magryta’s (‘24) graduation speech as support.

“We began high school in the era of COVID – with face masks and virtual classrooms, and we leave with TikTok addictions and a shared fear of eye-to-eye contact and in-person communication,” Bella Magryta said.

Her statement generalizes some aspects of the issue; some students coming out of the pandemic and back into synchronous school may not have returned with a TikTok addiction or social anxiety.

Data Supports the Decision

When announcing the new policy, CSD administration cited data for support and to educate Spartan families.

The first article the Parent Square post cited comes from The New Yorker and is titled “Jonathan Haidt Wants You to Take Away Your Kid’s Phone.”

There is an extent to which a title like that could be labeled ‘clickbait,’ and the interviewee is known for The Anxious Generation. A book like that might be critiqued for falling to pseudoscience or simplifying a complex topic, as it is a popular work on Goodreads with “psychology” and “self-help” genre tags.

As a social scientist, however, Haidt has some credibility to back up his general claim (featured in the article’s title) that kids should abstain from excessive phone use.

This policy seems like the type of position students would object to following. Phones are something proprietary for students and placing the device below the desk and craning one’s neck into it without the instructor(s) noticing is surely an already popular strategy.

Part of what could intensify the objections students may have is that rather than being forced onto the school by the state, it was their choice. This is contrasted by Florida where, according to the New York Times article, “School Cellphone Bans Are Trending. Do They Work?,” some states, like Florida, have set in motion state-wide bans.

CSD’s Policy Follows the “Basic School” Model

While school cell phone bans are trending throughout the country, Amy Tomalis, a CSD Upper School administrator, mentioned that the school’s policy was made to intentionally fit the specific concerns of CSD and its ‘Basic School’ educational model.

“

Instead of superimposing the cell phone ban policy over CSD, admin (like Tomalis) took care to allow feedback from school staff.

“We offered a ‘think tank’ this summer for staff who wished to have input on [the] policy,” Tomalis said.

Some people might critique school cell phone bans for excessively controlling student behavior or being draconian. However, that seems to be the opposite of what CSD admin intends.

“Many other schools were enacting full cell phone bans,” offering “punitive disciplinary actions if there were violations of policy,” Tomalis said.

While CSD seems to be a part of the grand sweep to restrict cell phone use at school, Tomalis holds some of the stricter methods of school cell phone bans in a negative regard, preferring a more moderate approach.

“We believe that punitive measures [don’t] teach [students] how to use cell phones appropriately, but rather enforce ‘not getting caught’,” Tomalis said.

For those concerned about how fast the times are changing, however, the July 24 Parent Square post had some good news.

“We know there will be some growing pains in this implementation” and “we appreciate your cooperation and support,” the post said.

Consistency and Habits Promote Learning

How much have people cooperated so far?

Some students (and teachers) wonder how much this policy will change the high school experience. Most classes strongly encouraged cell phones to be placed in the wall pockets both last year and even during the 2023 academic year. If students took their phones out during class, their phones would be taken.

But the penalties and repercussions were not clear or consistent. Some students simply would be given warning, pointing to an inconsistency in prior policy.

Indeed, Tomalis seems aware of the inconsistency in prior policy and considers it a good reason to employ a more centralized approach.

“

Patterson has “noticed a significant difference from when students held onto their cell phones to when they started docking them at the front of the classroom,” she said.

The difference she is referring to is the same one featured in her earlier answer. Students are more focused because the distracting phone-linked activities – listening to music, texting and checking social media – are less accessible when devices are set aside.

Some CSD teachers anticipated the change and put policy into place beforehand. Ever a proactive teacher, Patterson started requiring students to place their phones in pockets on the wall before she was required to do it. And they did not receive extra credit for doing what she felt was correct.

“I actually started doing this last year and was very happy to hear that it was going to be a policy across the board,” Patterson said.

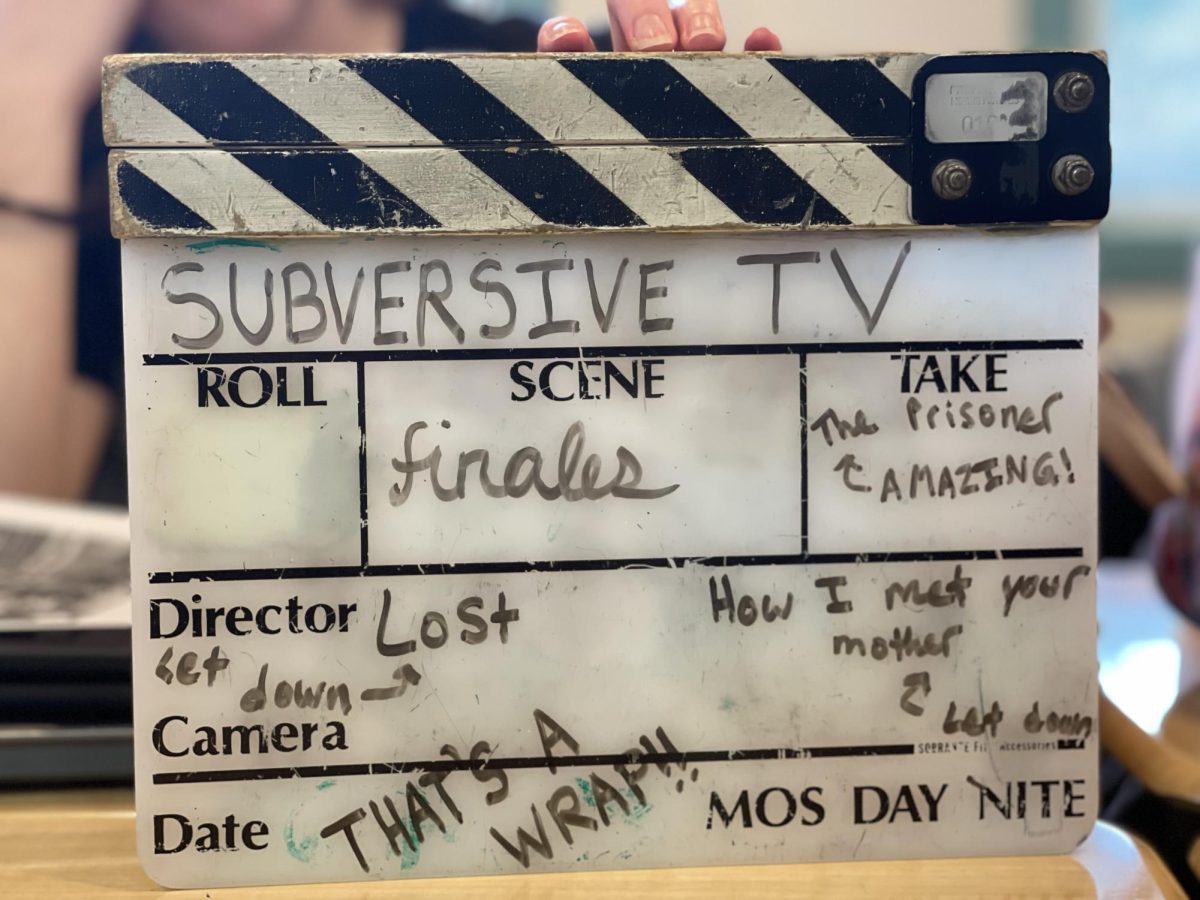

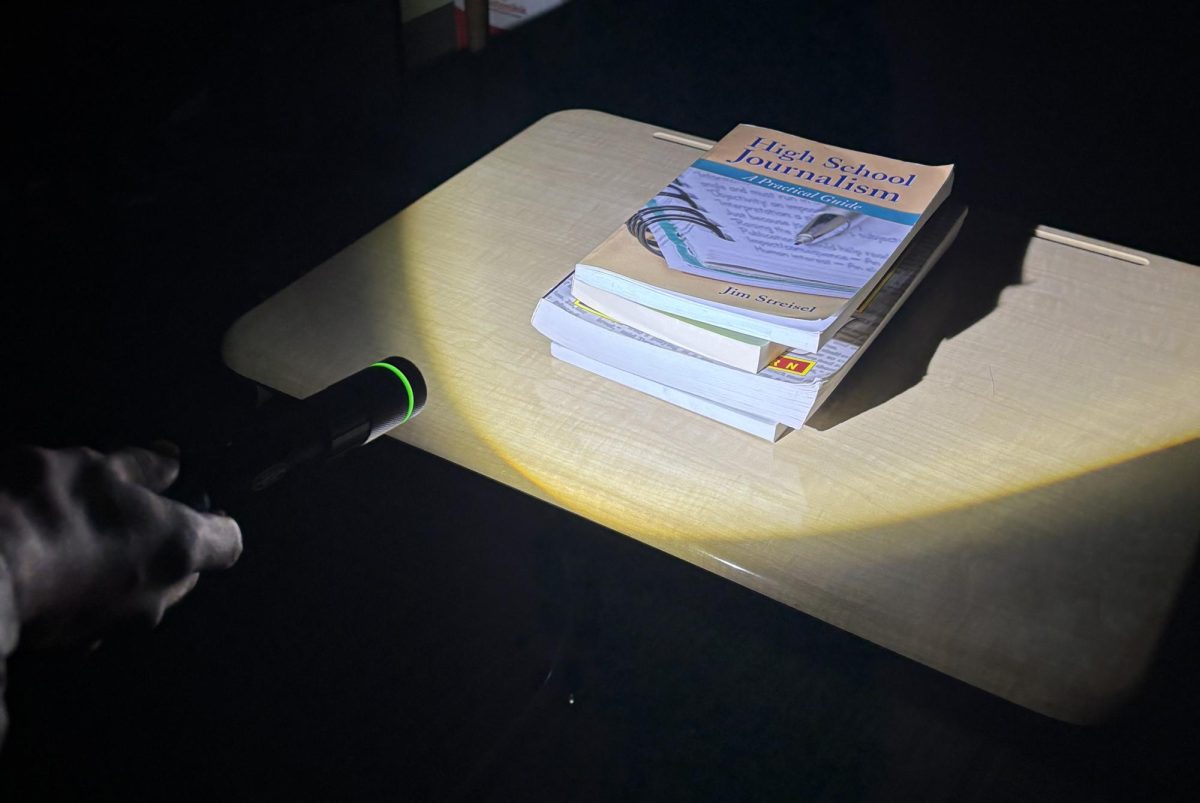

Two months into the new school year, there is still slight variation in the severity of the policy’s implementation. In Journalism class, for example, phones are often used to take pictures, record interviews, edit stories, post and review social media, listen to podcasts, etc. There are many possible uses for cell phones, and Mr. Mike Savicki, the Journalism teacher, allows students to explore them.

Of course, as with any new policy, there could be loopholes. Students could choose not to bring their phones to school to avoid having to place them in the pockets on the wall, and a limited number of students, furthermore, could keep their phones in their backpacks without the teachers catching them.

No Policy is Perfect

When asked about the flaws of the cell phone policy, Mia Kirsch (‘25) made several points.

In 2024, with so many issues around school safety, “If there’s an emergency situation, you may not have access to your phone,” Mia Kirsch said. “It [could] be a big safety issue.”

Part of where her alternate viewpoint originates is the contrasting approach of her old school compared to CSD.

“My old school’s phone policy was [that] we couldn’t have our phones out during any part of the day, including lunch. They didn’t take up our phones in class,” Kirsch (who oversees Arts & Entertainment for CSD’s Spartan Sentinel online news site) said.

Just a few weeks into the new school year, CSD high school experienced a local power outage and school was dismissed early. The main form of communication to both students and adults is by cell phone. With teachers in front of their classes without cell phones and students with their phones in classroom pockets, the message was slower to arrive.

Normally, the teachers would ask that the front desk be a conduit between a student and their parents rather than one’s own phone. That day, however, the students had to use their phones en masse because they couldn’t all line up and ask for the desk employees to pass messages.

The fact that the school allowed this and adapted to the latent pitfalls of their restrictive cell phone policy was nevertheless commendable.

Another oft-overlooked negative of the policy is the congestion it causes getting into and out of classrooms. Students often line up, each taking a few seconds to put their phones away, and the people in the back may not have enough room to get fully into the location. This may seem like a minor inconvenience but, class block after class block, and day after day, this congestion could lead to uneasiness and disruptions.

But while no cell phone policy will satisfy everyone all the time, Tate Bruns believes CSD’s “No Cells Bell To Bell” policy is working.

And Mia Kirsch, despite her reservations, much prefers this to the more restrictive and limiting policy of her old school.

By limiting distractions while also allowing students to learn more responsible cell phone use, perhaps there should be no reason for students to circumvent policy or push boundaries. Giving the policy a chance might not only lead to a better and more well-rounded high school educational experience, it could also help students gain life skills they can take with them to college or wherever life may lead after graduation.